Western Snowy Plover - Recovery Plan

(Charadrius alexandrinus nivosus)

Description and Ecology

What do they look like?

The western snowy plover is a threatened small shorebird, approximately the size of a sparrow. This bird is a small shorebird with moderately long legs and a short neck. Their back is pale tan while their underparts are white, and have dark patches on the sides of their neck which reach around onto the top of their chest. Juveniles are similar to non-breeding adults, but have scaly pale edging on their back feathers. Habitat choice and foraging motions often provide identification clues.

Things you need to know about their ecology!

During the breeding season, March through September, plovers can be seen nesting along the shores, peninsulas, offshore islands, bays, estuaries, and rivers of the United States' Pacific Coast. Plover nests usually contain three tiny eggs, which are camouflaged to look like sand and barely visible to even the most well-trained trained eye. Plovers will use almost anything they can find on the beach to make their nests, including kelp, driftwood, shells, rocks, and even human footprints. They are called shore birds because they are frequently found in open shoreline habitats, where they forage on small aquatic prey by picking or probing.

Geographic and Population Changes

To understand the Western Snowy Plover population you must know what factors can alter it. Snowy Plovers have natural predators such as falcons, raccoons, coyotes, and owls. There are lots of things other animals that eat these little shorebirds. There are also predators that humans have introduced or whose populations they have helped to increase, including crows and ravens, red fox, and domestic dogs. I’ve heard from my friend and lab mate who worked as for USFWS that the number one most destructive introduced animal that is hurting the snowy plovers population are ravens. Ravens have voracious appetite and can decimate a population in an area if left unchecked. Not to forget, humans can be thought of as predators too, because people drive vehicles, ride bikes, fly kites and bring their dogs to beaches where the western snowy plover lives and breeds. All of these activities can frighten or harm plovers during their breeding season.

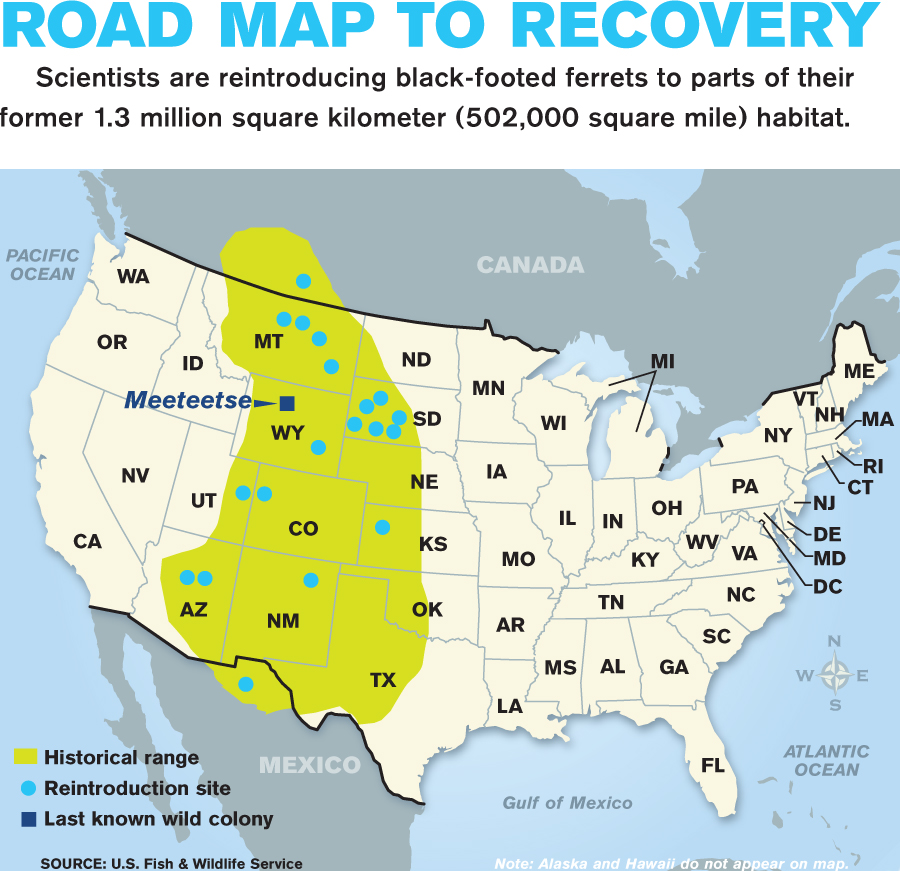

Illustrated above is a chart containing population densities of snowy plovers over the winter when these birds and many other species breed.

The highest density of the Western Snowy Plover occurs in California along the California coast but they also occur in significant numbers in others areas along the pacific coast. Other places where we find plovers are Oregon and even as far north as Washington. However they do not occur or at least establish colonies future than Copalis Spit in Washington.

Listing Date and Type of Listing

On March 5, 1993, the Pacific coast population of the western snowy plover (Charadrius alexandrinus nivosus) (western snowy plover) was listed as threatened under provisions of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.). The Pacific coast population is defined as those individuals that nest within 50 miles of the Pacific Ocean on the mainland coast, peninsulas, offshore islands, bays, estuaries, or rivers of the United States and Baja California, Mexico.

Above is a map of rage map for the Snowy Plover, which illustrates where the birds occur during specific times of the year and also were they occur year-round.

Cause of Listing and Today’s Threats

Snowy Plovers were listed for a number of reasons but the number one reason for their major decline was due to habitat loss for development. Other threats include:

- Oil spills

- Sea level rise

- Predators (natural and introduced)

- Invasion of non-native plant species into nesting habitat

- Human activity (today’s major threat)

Energy is very important to this small bird. Every time humans, dogs, or other predators cause the birds to take flight or run away, they lose precious energy that is needed to maintain their nests. Often, when a plover parent is disturbed, it will abandon its nest, which increases the chance of a predator finding the eggs, sand blowing over and covering the nest, or the eggs getting cold. This can decrease the number of chicks that hatch in a particular year. Did you know that a kite flying overhead looks like a predator to a plover? A kite over a nesting area can keep an adult off the nest for long periods of time.

Something special about the plovers is that they have many dense populations near San Luis Obispo. For example, in the Oceano Dunes State Vehicular Recreation Areas there exists and rather large population of Snowy Plovers. Above is a map nest locations provided by California State Parks.

Description of Recovery Plan

The recovery plan is divided up into three strategic steps:

a. Population increases should be distributed across the western snowy plover’s Pacific coast range.

b. Remove or reduce threats by conducting intensive ongoing management for the species and its habitat, and develop mechanisms to ensure management in perpetuity to prevent a reversal of population increases following delisting under the Endangered Species Act.

c. Annual monitoring of western snowy plover subpopulations and reproductive success, and monitoring of threats and effects of management actions in reducing threats, is essential for adaptive management and to determine the success of recovery efforts.

What can you do?

Volunteer to help protect the Western Snowy Plover. Here is a link to an interactive map to find opportunities at a beach near you! http://audubon.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=5502a94b595847e78beeec8c101f1a5b

References

California Department of Parks and Recreation, 2016. Nesting of the California least tern and western snowy plover at the Oceano Dunes State Vehicular Recreation Area, San Luis Obispo County, California 2016 Season. Unpublished Report, CDPR, Off-Highway Motor Vehicular Recreation Division. - GIS nesting site map

Western Snowy Plovers in California. (2015, October 26). Retrieved March 07, 2018, from http://ca.audubon.org/westernsnowyplover

National Audubon Society - information